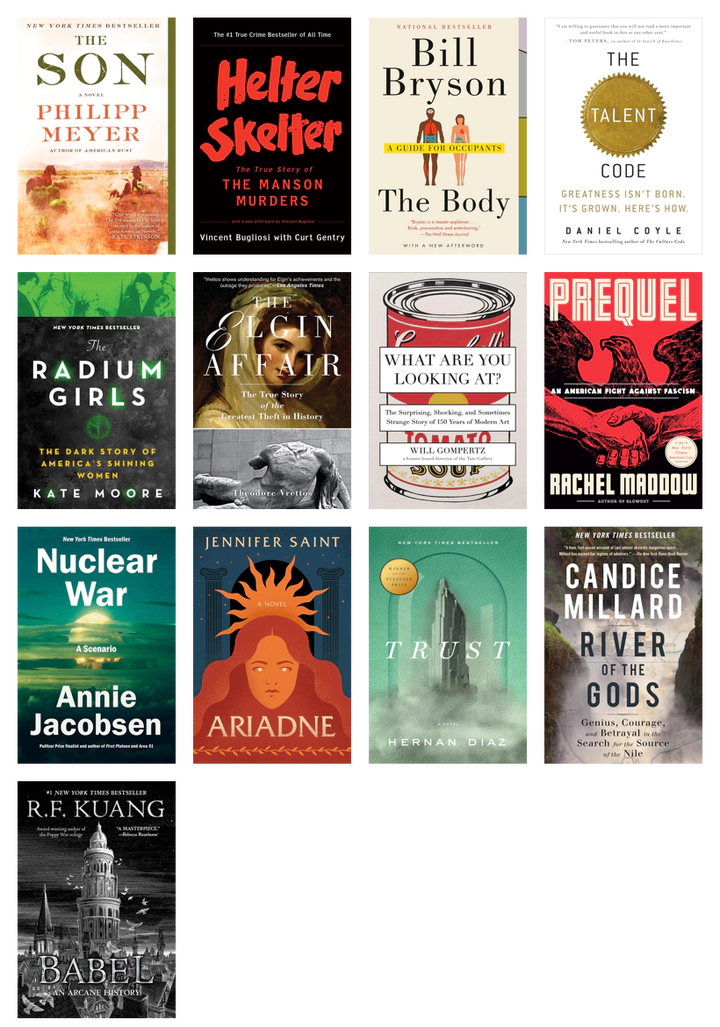

Books I Read in 2024

This year’s list leaned heavy. I didn’t plan it that way. But somehow I kept picking books about radiation, revolution, and the kind of history that doesn’t stay history.

Here’s what I read in 2024. Not all of it was good for my mood—but most of it was good for me.

Nuclear War: A Scenario

Annie Jacobsen

Jacobsen walks us, moment by moment, through a hypothetical nuclear exchange, modeled on real-world protocols and quotes from military planners who’ve spent their lives thinking about exactly this. The scenario begins with a single missile launch in North Korea. Spoiler-alert: everyone dies. Each step confirmed by declassified documents, technical manuals, and interviews with people who would know.

The Radium Girls

Kate Moore

It would be cool to know that my bones glowed in the dark; but, of course, they’re not supposed to do that. I mean, I want them do; but, not with the horrible suffering endured by the watch-dial painters in Morre’s The Radium Girls.

Moore lets the dread build with awful patience. The deaths are drawn in human detail: names, families, jokes made on the factory floor. A girl dies at 22, another’s leg breaks while she’s walking, another’s jaw comes off in the dentist’s hand. It’s truly horrifying. And, of course, it’s a story of American capitalism at its worst—a corporation exploiting young, mostly teenage, women without any recourse or justice.

Ariadne

Jennifer Saint

I was semi-familiar with the Ariadne myth before reading this. Saint doesn’t revise the myth so much as slow it down until you can feel every betrayal settle in. Ariadne is given space to second-guess, to mourn. The way Saint portrays Dionysus (Ariadne’s savior-husband, turned betrayer) is particularly poignant for the modern household.

Babel, or the Necessity of Violence

R.F. Kuang

What if words were literal magic? That’s the basic premise that underlies this book. I was hoping it would be a little more ✨_magical_✨ that it actually was. You see, I was a child whose brain formed around the video game MYST. And you are either a child whose brain formed like mine, or you are not. Sadly, those of you who are not, missed out on a baffling world of words and puzzles and mystery. I wanted this book to be like (a better) novelization of MYST. (You see, MYST was novelized; but, it was bad. Don’t read the book. Play the game. The better story is in the game.) Anyway, this book was its own thing. It’s about words and has a magical-realism aspect to it; but, it’s also about empire and colonialism. I liked it, even though it wasn’t about MYST at all.

Trust

Hernan Diaz

This book won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2023. The story is told four times, each iteration refracting the same story—a wealthy financier and his mysterious wife—through memoir, fiction, ghostwriting, and notes. What hit hardest was how quietly devastating it is to watch a woman be erased not with violence, but with structure. There’s also a clever musical element that comes in at the end. I’m a sucker for that.

Helter Skelter

Vincent Bugliosi

Bugliosi, the prosecutor in the Manson trial, walks through the murders, the investigation, the courtroom theatrics, and the strange, almost comic banality of evil. Charles Manson wasn’t an evil genius, he’s petty, manipulative, and foolish. It’s frightening because of how little it took to make others follow him.

By the midpoint, I wasn’t reading for suspense. I was reading to see if anyone would act like a person. Mostly, they didn’t. The book is a slow, detailed record of failure—of institutions and of humanity.

Charles Manson was a bad guy. That’s the moral of the story. But, his crimes were hardly the result of “satanism” or “mind control” or whatever is thought about him today. He was just an asshole.

Prequel

Rachel Maddow

Prequel documents how fascism flirted with power in the U.S.. Industrialists, media figures, and politicians all played a part. We’re seeing a lot of the same playbook today.

River of the Gods

Candice Millard

There’s something both majestic and bitter about this book. On the surface, it’s about the race to discover the source of the Nile. But underneath, it’s about the high cost of hubris. And, I guess, the best part is that neither of the deeply flawed main characters actually found the source of the Nile, a fact that the native people had already discovered centuries before white explorers showed up.

The Body

Bill Bryson

Bryson’s best book, A Short History of Nearly Everything is one of my favorites; so, I thought that this would be a fun way to read about the inner workings of the human body. And it was! This book reminded me that being alive is wildly improbable. And that none of us know enough about what’s happening under our own skin.

The Son

Philipp Meyer

The Son tells the story of three generations of a Texas family: Eli, the patriarch, who survives a Comanche kidnapping and becomes a myth; Peter, his guilt-stricken son, who documents the family’s sins; and Jeanne Anne, the heir who inherits the wealth; but, it does not bring her peace.

The Talent Code

Daniel Coyle

Coyle’s thesis is simple: talent isn’t something you’re born with; it’s something you build. And the way you build it is through “deep practice”: slow, focused, error-filled repetition that thickens neural wiring and makes skill stick. He talked a lot about myelin, which is an insulating layer of fat that forms around nerves. It turns out that the more you use a nerve, the more myelin you grow around it, increasing its stability. The electricity traveling along the nerves is moves faster with more myelin. Which is just a neuroscience-y way to say that the more you do a thing, the better you get at it. That’s pretty much the only way the brain learns new things: repetition. Duh!

Anyway, there’s no secret code. You have to practice. Slowly, with focus, over and over.

What Are You Looking At?

Will Gompertz

If you know me, you know that I’m kind of a modern art fan. I won’t call myself a scholar; but, I have written about Surrealism quite extensively. I’ve read a lot of books on modern art; but, if you’re just trying to wrap your mind around why Duchamp’s Fountain is a work of genius (when you might not even think it’s a work of art at all), then this book is for you. Gompertz shares a similar view on many of the major works that I hold; but, he explains them with joyfulness and without talking down.

The Elgin Affair

Theodore Vrettos

There’s a moment in this book where Lord Elgin describes his actions as “saving” the marbles from the Ottomans. That’s really when you can test the limits of how far you are physically able to roll your eyes. Elgin, a British ambassador, removed half the sculptures from the Parthenon under dubious permissions and shipped them to London. The British Museum still has them. This isn’t just a story about theft. It’s a story about how museums justify it, how governments codify it, and how the word “preservation” can mean almost anything when spoken in the right accent.